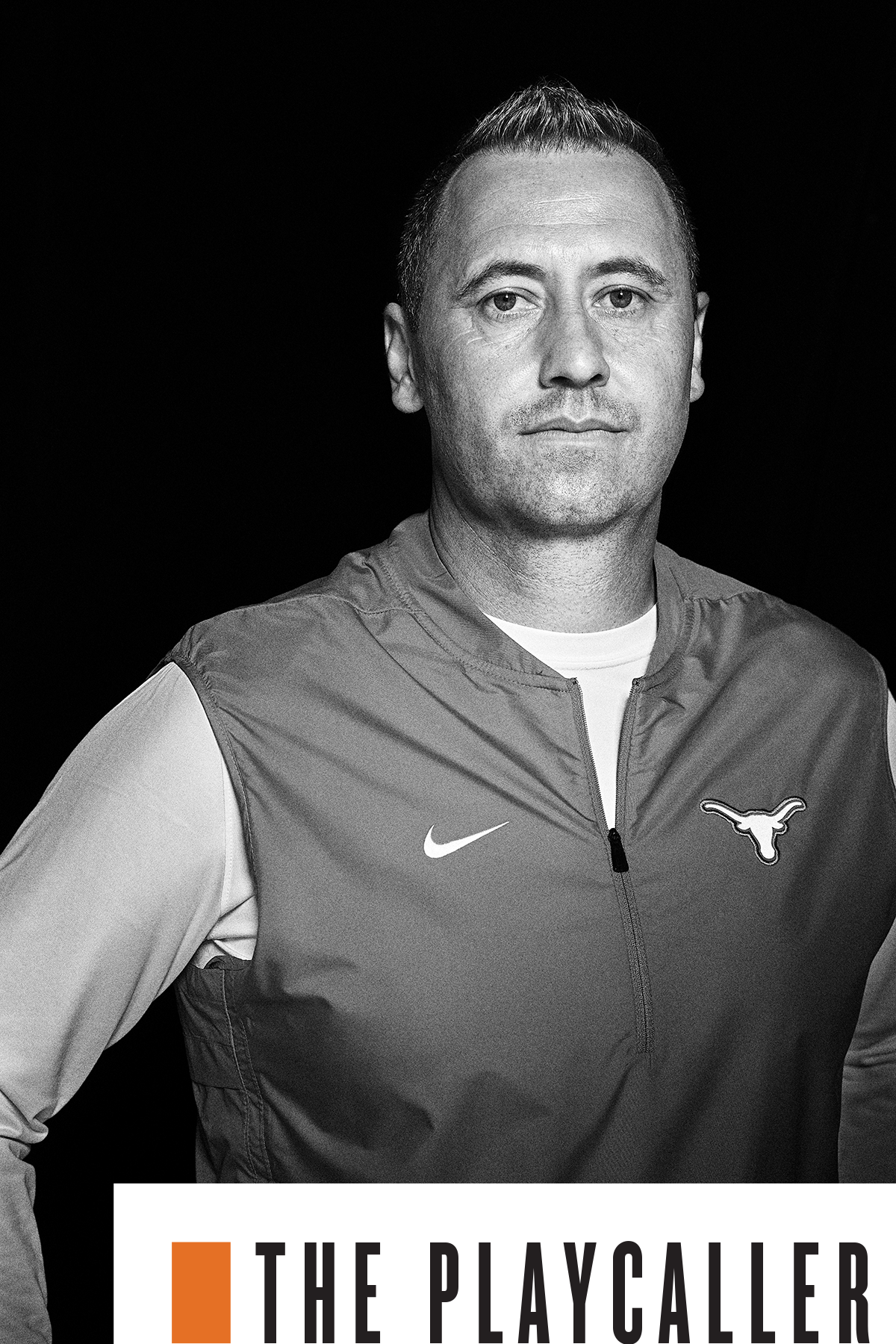

Steve Sarkisian’s path to Texas football glory is paved with offensive wizardry—and a heavy dose of self-reflection.

By Chris O’Connell

Photographs by Matt Wright-Steel

For as many touchdowns as the quarterback scored in his career, if you type “Vince Young touchdown” into Google, one dominates the results. You know which one.

The result is at once the greatest sports moment imaginable for almost every living Texas football fan and a stinging reminder of a bygone era, when it wasn’t out of the realm of possibility to witness gridiron transcendence in burnt orange and white. Everyone reading this magazine has this play seared into their cortexes, so I won’t mar it with my words, but because of the last 15 years—including one other championship game that no one wants to talk about and a whole lot of heartbreak—the experience of watching that famous play is a mixed bag of emotions.

If you squint hard enough at the 2006 clip, you might be able to see Texas’ new head football coach on the opposing team’s sideline. Steve Sarkisian is next in a long line of head football coaches tasked with bringing the Longhorns back to this vintage ideal.

And that was an era of Sarkisian’s life he would probably like to forget. After that crushing loss to Texas, his career took off like VY on fourth and five—except he crashed at the goal line. After being elevated to offensive coordinator at USC, he became head coach at Washington, where the quarterback whisperer turned dual-threat Jake Locker into a star. Then he bounced back to USC for a crack at returning the legacy program to glory. He was fired midway through his second year after slurring his way through a booster event, missing a practice, and reports from his assistants that he was intoxicated during a game. When he entered rehab in 2015 it was unclear if he would ever be given such responsibility again.

But arriving on the Forty Acres this winter to take the biggest job of his coaching life, living out of a room at the AT&T Executive Education and Conference Center, one of the first things he did was watch a replay of that very National Championship game. For him, that play—and that chaotic era of his life—is a wound that is healing. Finally.

“I was looking to see if you could see me on the sidelines with my head down,” Sarkisian says, with a smirk.

He even pulled on the scab again when he first met Michael Huff, BS ’05, a member of that Longhorns team that beat USC and one of just a few holdovers from Tom Herman’s staff. Huff tells me Sarkisian broke the ice while Huff, assistant director of player development, was hanging out with Young, BS ’13, Life Member, and Colt McCoy, BS ’09.

“The first time I met him he told us about the heartbreak of what we did to them in the national championship game,” Huff says. “We were joking and laughing.”

He can laugh at himself now. After hitting rock bottom, Sarkisian, 47, is now standing on the mountaintop. He’s college football’s patron saint of second chances, the man whose Texas hiring launched a million redemption stories, even if he doesn’t quite agree with the notion.

“I’ve never looked at it that way,” Sarkisian says. “Whatever was supposed to happen was going to happen as long as I put in the work on and off the field.”

Sarkisian’s office is a temporary space on the seventh floor of the North End Zone being utilized for football staff while Moncrief undergoes renovations. He has a mini-fridge with snacks and some scattered tins of Grizzly Dark wintergreen chewing tobacco strewn about, globs of which he nonchalantly spits between answers, into a receptacle I never see. It’s rather elegant as expectorating goes, as if he’s spitting into eternity.

“Through it all, I was able to work my way back to where I wanted to be and where I thought I could be and should be,” Sarkisian says confidently, after a spit. “The approach and how I got there was very different, and I think the sustainability and consistency of success will be different too.”

Sure of himself as he is—would you want your next head coach any other way?—Sarkisian is perhaps the most acutely aware of his previous failures and personal demons of any coach in America. That self-recognition is a feature then, instead of a bug, when it comes to rebounding after a heartbreaking loss or proving with conviction to a recruit’s parents that he truly does have their son’s best interests in mind. He’s been there before; he’s torn himself apart and built himself anew, like some sort of pigskin Robocop.

For as much as he’s seen and as low as he has been, he doesn’t appear to be jaded about the rah-rah spirit of college sports. In fact, he looks at the majesty and pageantry of The University of Texas with the wide-eyed wonder of a toddler hopped up on Dole Whip at Disney World. Sarkisian was truly moved by the success of the three spring national champions and by the deep tournament runs by other Longhorn teams. Holed up at the hotel with his wife, Loreal, he says he had Longhorn Network on a loop, leaving his home to see a lit-up UT Tower at night after another room service order.

“Those moments I’ll hold on to forever. When I got here, I was really here,” Sarkisian says, emphasizing that last sentence with a few raps on his wooden desk. “I’m getting the chills right now.”

If it sounds corny, or like a load of longhorn dung, Huff insists that Sarkisian is the same guy every single day, from his introductory press conference, to—in Huff’s words—“after we win a national championship.”

“Everything he’s been through has set him up for this moment,” Huff says. “He’s transparent.”

January 2, 2021, was a busy day for UT Vice President and Athletics Director Chris Del Conte. After coming to terms with Sarkisian, the firing of then-current head coach Herman, MED ’00, Life Member, triggered a $15.4 million buyout, plus $9 million in buyouts for his staff. Sarkisian then signed the most lucrative coaching deal in Texas history: $34.2 million guaranteed over six years, two dealership cars, 20 hours of private airplane use each year, a relocation bonus, plus performance escalators and a potential lump payout of $1.2 million if he’s still coach on New Year’s Eve of 2024.

Previously, Sarkisian interviewed for the head coaching position at Colorado after the 2019 season but withdrew his name from consideration before an offer arrived. He was rewarded with a raise at Alabama and his first national championship as a coach at any level. His patience also made him one of the hottest coaching candidates in the country, hence that hefty contract. Though he was an outsider—a mostly West Coast-guy with some recent stops in the deep south but little connection to the state of Texas—Sarkisian felt his first head coaching job since his unceremonious firing by USC in 2015 had to be here.

“I had some other job opportunities present themselves but they didn’t feel like the right fit. So, when this job came, more so than feeling redemptive it felt like ... this is it,” Sarkisian says. “The light came on. This is the one.”

For a guy who had never pressed his pristine Jordans (Huff, who owns a sneaker store in Dallas, is his main hookup) to Austin soil once in his life, Sarkisian’s Tour de Forty Acres was like 10 pounds of cowboy queso in a five-pound tub. One of the first things the new football coach did upon arriving in Austin was hightail it out to the Governor’s Mansion to meet Gov. Greg Abbott, BBA ’81, Life Member, Distinguished Alumnus. The meeting doesn’t quite have the folkish charm of the tales of Darrell K Royal and Lyndon Baines Johnson playing 18 holes before rambling out to Kerrville to catch some grade-A guitar picking on folding chairs, but the parallels are there. Famous Texas politicians like to be next to that burnt-orange glow: LBJ with DKR, George W. Bush with Bevo, and now Abbott with Sark. Perhaps most strikingly is that Sarkisian, unlike Herman, Charlie Strong, heck, even Mack Brown or the couple guys before him, was famous before he signed on the dotted line. Play-catch-with-the-governor-type famous.

So that’s what they did. Sarkisian, the first Texas football coach to have previously head coached at what we’ll call a Major Football School since Dana X. Bible came to Texas from Nebraska, tossed the pigskin around with perhaps the most famous governor in America on his porch. Sarkisian said they chatted about recruiting and the state of the program, which hasn’t won the Big 12 conference since Abbott was Texas Attorney General and Sarkisian was coaching at Washington.

Next was a meet-and-greet with Bevo, the only famous longhorn in America, which isn’t a slight against the 1,800-pound bovine.

“What a massive animal … the horns?” Sarkisian says, almost as if he still can’t believe what he saw. “There’s something special about that.”

That night, after Sarkisian’s introductory press conference, a big group met on the office veranda of UT Austin President Jay Hartzell, PhD ’98, Life Member. Sarkisian remembers gazing up at the Tower, which was wholly unfamiliar to him at the time.

“I thought, That’s a really nice tower,” Sarkisian says. “I didn’t know. OK, I guess that’s the center of campus.”

Then his phone started lighting up. Friends from Austin had seen the Tower lit burnt orange and knew he was in town.

“They are really excited to have you!”

“You’re a big deal!”

“Wow, they lit the Tower!”

Sarkisian leaned over to Vince Young and asked, “What’s the significance here?”

“That’s a big deal, if they light it for you,” Young told him. “That’s for championships.”

Longhorn Nation will forgive Sarkisian his ignorance of the Tower’s significance if he can figure out a way to keep the lights on.

Growing up in Torrance, California, a coastal town on the edge of Redondo Beach, Sarkisian says his first memory of football was watching Bears running back Walter Payton leaping over a pile of bodies into the end zone. It’s a pretty routine-sounding highlight for Sweetness, but for the young Sarkisian, it was a formative moment. He ran upstairs and started leaping over his parents’ bed, pretending he was Payton, which he did so many times that he eventually destroyed the frame. He pined for the jerseys of his favorite players and made up football scenarios to run through and then execute them. Sally, a homemaker, and Seb Sarkisian, an engineer, moved from Boston to California between their sixth child and Steve, their seventh and youngest. Despite growing up in a large family, his closest sibling in age was five years older, and Sarkisian was forced to create fun on his own.

“I felt like I was Bugs Bunny,” he says, referencing “Baseball Bugs,” an episode of Looney Tunes in which our hero plays every position on the diamond against the Gashouse Gorillas. “I was quarterback, running back … [I was] on defense, but I was playing games by myself.”

Sarkisian excelled at both football and baseball at West High School, but baseball led him to a short stint as a non-scholarship shortstop on the USC baseball team in the fall of 1992. After a semester, blocked by future second-round draft pick Gabe Alvarez at the position, Sarkisian transferred to El Camino Junior College near his hometown. While on the baseball team in 1993, Sarkisian met the man he considers his first football mentor, El Camino head coach John Featherstone, who convinced him to give football another shot.

“What I loved about him was his energy ... I want to be like that guy,” Sarkisian says. Featherstone, who had a locker room full of white beach bums, Black players from L.A., and Polynesian athletes, inspired in Sarkisian a sense of creating relationships between people of different backgrounds.

“That set the tone for me about team and culture,” Sarkisian says. “We loved each other. And it was only a JuCo.”

After two standout seasons at El Camino, Sarkisian transferred to play at BYU under his second mentor, the offensive innovator LaVell Edwards, who showed the young quarterback how to instill confidence in players.

“Coach Edwards was the master of that. He was so mellow and calm. He was old but he was the coolest guy,” Sarkisian says. “He walked on the field and we knew, from him, that we were going to play really well.” One day, Sarkisian played so well under Edwards that he became a household name.

On August 24, 1996, during Sarkisian’s senior season, the Cougars began the year with a 10 a.m. kickoff against No. 13 Texas A&M in the nationally televised Pigskin Classic. In the fourth quarter, with the score knotted at 34, Sarkisian rolled left, throwing across his body to hit wide receiver Kaipo McGuire for a huge gain. It’s the throw every quarterback is told not to make, and yet—and yet!—Sarkisian played against type to his great benefit. No one will mistake Sarkisian for Patrick Mahomes, even in the grist of standard definition, but his systematic deconstruction of an Aggie defense that included multiple future NFL All Pros and eventual College Football Hall of Famer Dat Ngyuen is astonishing, even 25 years later. That he broke the rules of quarterbacking along the way foreshadowed a career in coaching quarterbacks to do just that.

With a minute and change remaining, and BYU trailing by three, A&M rushed just four players on first down, employing a “bend-but-don’t-break” style of late-game defense. Let the kid toss a couple over the middle, he’ll run out of time, and we’ll escape Provo intact. But Sarkisian spotted a mismatch on the outside. As he took the shotgun snap, he was already taking three steps back and winding up. He uncorked a spiral that dropped directly into the outstretched hands of K.O. Kealaluhi—a receiver whose name should have written a thousand Sunday-morning sports headlines—who slid into the end zone. Ballgame. The Pigskin Classic wasn’t just a clever name.

All told, Sarkisian threw for six touchdowns and 536 yards that day, in an era when players were still wearing the Beyond Thunderdome shoulder pads and most coaches looked like Ed Koch. Under Edwards, who mentored Hal Mumme and Mike Leach, leading to the Air Raid (and, thus, Patrick Mahomes), Sarkisian authored an iconoclastic brand of anti-football. That is, a version of the game that bared little resemblance Darrell K Royal’s “three outcomes” ground-and-pound wishbone.

“One thing to remember is when BYU gets rolling on offense, it’s kind of hard to stop the train,’’ Sarkisian told a reporter for The New York Times after the game, which isn’t technically the first instance of his now-ubiquitous #AllGasNoBrakes mantra, but it’s close.

Sarkisian was now a known quantity across college football, eventually winning the Sammy Baugh Award and appearing on the cover of a December issue of TV Guide. The Cougars finished 14-1, winding up as AP’s No. 5 team behind Sarkisian’s cunning and efficiency, a harbinger of what would come as an offensive mind on the sidelines.

Back in his office in June, Sarkisian laughs as he recalls visiting his childhood home as an adult, where that football mind was first formed. He remembered a cavernous Soldier Field, and he, the avatar of Walter Payton, ready to hop the pile once more.

“It felt like this huge space, but I go back and it’s this small hallway,” Sarkisian says. “I was just a little kid with a big imagination.”

That imagination earned Sarkisian some primo offensive coaching positions. After an underwhelming three-year stint playing in the CFL for the Saskatchewan Roughriders, in 2000, he found himself back at El Camino. While working in sales at an internet startup, he started coaching quarterbacks in a volunteer capacity under his mentor Featherstone. Encouraged by his former coaches to keep at it, his offensive coordinator at BYU, Norm Chow, introduced him to USC head coach Pete Carroll and helped him land a graduate assistant position there.

“Pete Carroll got my career to take off,” Sarkisian says, of the third mentor in his football life. “The way he went about it, the long talks and projects he’d give me. The biggest thing I got from him was he taught me defense. As much as I knew offense, he taught me defense.”

Within another year he was quarterbacks coach, working with Heisman Trophy-winner Carson Palmer, and by 2004, he was in Oakland coaching with the Raiders, before bouncing back to USC, with a promotion: associate head quarterbacks coach. But Sarkisian so impressed notorious Raiders owner Al Davis in his one season in Oakland—and his work with another Heisman Trophy-winner in Matt Leinart—that Davis offered him the head coaching job at the age of 32.

Sarkisian turned Davis down, saying he just didn’t feel like it was the right time to be taking that job. Now a scorching-hot coaching candidate in both college and the NFL, Sarkisian parlayed the offer into another promotion, becoming USC’s offensive coordinator. Successful both in 2007 and in 2008, Sarkisian’s lasting effort was in his final season as OC, transforming once-backup QB Mark Sanchez into a superstar. Sanchez’s 2008 turnaround under Sarkisian was so stark—34 touchdowns, 3,207 passing yards, 65.8 percent completion rate—that he became the first USC quarterback to leave school early in almost two decades, much to Carroll’s chagrin.

Before that year’s bowl season began, though, Sarkisian was already out the door, headed north to take over a Washington team that had just completed an 0-12 campaign. Though the Huskies would win only five games the following year, it was a drastic turnaround that included a last-second win over Sarkisian’s former team, No. 3 USC. He increased that win total the following season by two, but after three straight 7-6 finishes, Sarkisian was derisively nicknamed “Seven Win Steve” by the local press.

Still, the head coaching job at USC always seemed like it was Sarkisian’s to take. Carroll had left for the NFL after Sarkisian’s first season in Washington amid speculation that Sarkisian would bounce directly back to Pasadena like a pinball. Sarkisian didn’t feel right leaving Washington so soon, but after Lane Kiffin was famously canned on the LAX tarmac at 3 a.m. following a brutal loss to Arizona State in September 2013, the USC talk heated up again. Three months later, Sarkisian accepted the job as USC’s head coach, choosing to call plays as well.

“I am extremely excited to be coming home to USC and for the opportunity that USC presents to win championships,” he said in a statement upon his hiring. “I can’t wait to get started.”

Sarkisian’s tenure was marred before it really began, though. USC was coming off a period of draconian sanctions that included foregoing bowl games and scholarships and vacating more than a dozen wins, including the 2004 BCS Championship. (USC would later charmingly—for Texas fans—attempt to vacate its loss to the Longhorns the following year; the NCAA does not mandate that teams vacate losses.)

Once again, Sarkisian was in rebuilding mode. Before his first game at USC, he made news when senior cornerback Josh Shaw, the team’s defensive captain, injured his ankle in what he said was an attempt to save his nephew from drowning. But when Shaw’s name appeared on an LAPD incident report from the same night, Shaw admitted he made the entire story up and Sarkisian suspended him. Two weeks later, Sarkisian was in the news again. During a September game against Stanford, refs called Sarkisian for an unsportsmanlike-conduct penalty, after which the coach beckoned for USC Athletics Director Pat Haden, who got into a heated argument with officials. Pac-12 Commissioner Larry Scott reprimanded Sarkisian and Haden—who was also fined $25,000—for “inappropriate sideline conduct.”

“It is my job to manage the game, not Pat’s,” Sarkisian said in a statement. “For the good of the game, I will be better on this in the future.”

It never got much better. After capping off the 2014 season with a win over Nebraska in the Holiday Bowl to finish a respectable 9-4, the wheels started coming off in Sarkisian’s personal life. While it wasn’t public knowledge at the time, later reports—specifically those from players and expense reports from his time at Washington—revealed that Sarkisian had a problem with drinking, and that it was creeping into his work life. That offseason was the Salute to Troy booster dinner that sealed his fate in Pasadena.

Carroll reached out to his former assistant after his firing and told ESPN that he was pulling for Sarkisian’s recovery. “It breaks my heart to see how this has gone,” Carroll said. “But he recognizes it and he’s going to do something about it, so this is the day the turn occurs.”

In October 2015, Sarkisian was watching an ESPN editorial about star Yankees pitcher CC Sabathia withdrawing from the MLB playoffs to voluntarily attend rehab for alcohol. A light turned on in Sarkisian’s mind. “I knew I needed to [go]. I didn’t know how to go about it,” Sarkisian told ESPN in 2017. “But that thing gave me a feeling of, ‘There’s a like person that is going to do this. I know I need to do it. Now how, what, when.’ So I made the decision to go do it. It’s been the best decision of my life.” Sarkisian has said he still regularly attends Alcoholics Anonymous meetings.

A year later, Alabama coach Nick Saban gave Sarkisian his second chance at coaching, offering him a spot as an offensive analyst on his staff. (Positions like this on Saban’s staff are popular landing spots for exiled coaches, including some familiar names like former Texas player and assistant coach Major Applewhite, former Texas head coach Charlie Strong, and current Texas offensive coordinator Kyle Flood.) In Saban, Sarkisian got his fourth mentor in football.

“I also learned the discipline needed in football. We all want to have discipline on the field but it starts off the field,” Sarkisian says. “He is the most disciplined human being I’ve ever met in his approach.”

Saban elevated Sarkisian to offensive coordinator for the national championship game in 2017 after Lane Kiffin departed, which led to the same position with the Atlanta Falcons the next season. He lasted two seasons in the NFL, bouncing back to Alabama after his firing on New Year’s Eve 2018. Carroll again rooted publicly for his protégé, telling the media at that year’s NFL Combine, “he’ll do great.”

Just three years after a very public firing threatened to destroy his career, Sarkisian was offensive coordinator at the best program in college football. Working with quarterbacks Tua Tagovailoa and Mac Jones, Alabama elevated its already high-powered offense to win the national championship in January 2021, just a few days after Sarkisian accepted the Texas job. Just before the game, the media asked Saban how he felt about Sarkisian leaving for his first head coaching job in five years. He was—in his own way—effusive in his praise.

“Sark is the one guy that has shown great maturity, I think, in how he’s handled his situation, moving on to be a head coach, which is what he’s worked for, and we’re happy for him relative to the opportunity that he’s created for himself by the great job that he’s done for us here,” he said.

The game, in which Alabama’s offense scored seven touchdowns, was watched eagerly by every Texas fan from Austin to Zagreb. Sarkisian’s deft play calling left Longhorn Nation’s collective mouths watering. I ask Sarkisian to explain his offensive philosophy to me. How does one become the sage of the spread offense, the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi of beating the absolute hell out of, say, Oklahoma?

“Implementing an offense is a science. Calling a game is an art,” Sarkisian explains. “I don’t believe that in game-calling it’s two plus two equals four. There’s an art form to it, there’s a feel to it. There’s gut instinct. There’s setting things up. It’s combining the two. Science is the foundation of how we operate, but yet there’s an art form to the flow of the game.”

[Spit.]

Here we go again, right? You’ve heard it from this very writer before: This guy is different from the last guy. Texas is back. Oklahoma is doomed.

Part of being a Longhorn fan is willful ignorance about your own shortcomings. But there are some incontrovertible facts about this football program: Texas is 70-53 over the last decade, with just one top-10 finish during that period. That’s the losingest stretch of Texas football since the 1984–93 span, in which Texas also went through three coaches but at least brought home one conference title. The Longhorns have not produced a first-round draft pick since 2015, when Malcom Brown was the final pick on day one. Since the College Football Playoff began in 2014, Texas has never finished higher than 15th in the final rankings while the following teams have: Baylor, TCU, Kansas State, Oklahoma State, Iowa State, Texas A&M, and, of course, Oklahoma, who has made the playoff four times. This is still one of the best jobs in college sports, but living up to expectations can be downright Sisyphean.

Sarkisian doesn’t balk at the challenge.

“When you go somewhere where they know what success and championships look like, it’s a little easier to get back. There’s a path that’s been paved. Maybe we have to re-pave it or clear some weeds,” Sarkisian says, “but that part’s exciting.”

When I first started profiling Texas head coaches, my daughter was a newborn. This is my third trip around the coaching carousel and she’s only about to start second grade. Some kids spend their entire childhoods under one regime; my daughter just figured out how to do the Hook ’em Horns hand sign after I tried to teach her under Strong and Herman.

What every alumnus wants—needs—to know is: Can this guy win consistently, to the point where Texas fans don’t feel queasy at the thought of ... Iowa State? Even with an expanded College Football Playoff field, can Texas still compete on the national stage? Will Paul Finebaum ever eat chicken-fried crow?

Great men with big offices on the south end of the stadium have been humbled before by high-flying Big 12 offenses, recruiting fiascos, song lyrics. But Sarkisian says one of the reasons Texas felt right is that he understands what is expected of him. He doesn’t need to rebuild a ruinous program, like he did at Washington, to teach a generation of fans how to love football or a team how to think about greatness.

“I don’t have to come in here and retool a mindset and a vision,” Sarkisian says. “There’s a path that’s been laid here over decades, and it’s our job to make sure we get back on that path because there’s a great deal of pride in this program, this university. Ideally that’s what we end up doing. We compete for championships every year, we end up in the college football playoff, ultimately we end up winning a national championship or more.”

Ted Koy, the wide receiver who won a national title under Royal and played in the NFL for the Raiders and Bills, has four quick words for me when I ask him about Sarkisian: “Quality man, quality coach.” The “man” portion comes from Sarkisian’s insistence in embracing Texas’ winning past and attempting to fuse it with the culture of a team that would love to play in a bowl game not named Texas or Alamo. Koy says Sarkisian immediately initiated an open-door policy with football lettermen around the program.

“I don’t have any rights to be there. My time has come and gone, but for me being welcomed back is very honoring,” Koy says, “and that’s an extension of Coach Sark. He is really honoring us older guys.”

Huff says that, in addition to Sarkisian’s whirlwind first day on campus, he insisted on holding Zoom meetings with former players who he wanted to build relationships with and have back on campus. He mentions a few guys who can be identified without last names who have already been around the team in significant ways: Earl, Ricky, Vince, Colt, plus many other lettermen.

“That’s what it’s supposed to be. A lot of them live in Austin but haven’t been in the stadium in two, three, four years,” Huff says, incredulously. “How do you live in Austin and you haven’t seen the stadium in two, three years? That is one of the things that has not been right around here and one of the things he wants to fix.” Sarkisian learned how to cultivate relationships from Featherstone.

Both Koy and Huff have observed moments in practice that have impressed them. Huff, a former defensive back who pays close attention to that position group out of habit, singles out Sarkisian’s work with D’Shawn Jamison. The senior cornerback has turned heads primarily on special teams as the Longhorns’ primary kick and punt returner. But Sarkisian, Huff says, is convincing Jamison to “not just be happy returning kicks … winning the Thorpe Award, returning kicks, maybe winning the Heisman. Seeing the bigger picture.” It’s like the shot of courage that LaVell Edwards gave Sarkisian at BYU.

At one practice, Koy saw wide receivers coach Andre Coleman correct a player after running a bad route. Sarkisian came over and added his comments. The very next play, the receiver ran it perfectly. Koy smiled as he watched Sarkisian sprint across the practice field to praise his adjustment. Similarly, he witnessed Sarkisian address the team at the end of one practice, telling the players they had to finish each practice like it was the fourth quarter of a game—to fight through fatigue and cut down on mental errors.

“At the next practice, something happened—he really came down on the team,” Koy says. “I thought, that’s fair. He told them they needed to pick up the pace at the end of practice and they didn’t. They need to be called out on that. That’s the consistency I recognize.” Koy tells me that he normally refrains from comparing head coaches to one another, but that Sarkisian, particularly that consistency, reminds him of Royal.

There’s one moment in my conversation that makes me believe that Sarkisian is different (and if I’m wrong, my email is easy to find). As we chat about offensive schemes and his personal growth, the themes begin to meld. In AA, those in recovery are taught to live one day at time. In practice, this means living in the moment and not putting too much stock into what has come and what will be. I ask Sarkisian if that same mindset has helped him grow on the field.

“I think so. I leave my ego at the door now. I think it used to be more about me, quite frankly—I used to worry about me and how I felt. I shifted my focus to others. By doing that, I feel pretty good,” Sarkisian says. He spits once more, collecting his thoughts. “I end up feeling the way I probably wanted to feel my first time around as a head coach.”